Looking Back at the “Top Toymaker’s Buying Guide” from Life Magazine

There are moments when I’m taking advantage of the tools of the future that I sometimes stop and ask: “How much better would today be if the people of yesterday had had access to this exact same toolkit?” Can you imagine what journalists and writers of the fifties would have crafted if they’d had access to Google? Just how many amazing essays and books would they have produced sixty years ago if, at a moment’s notice, the writers of the time could have instantly searched through man’s written works? I think it’s easy to forget how fortunate we are these days.

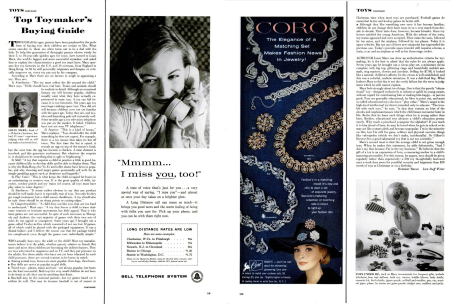

Bloggers who are not deep diving into the magazine, book, and newspaper archives that Google has opened up to us are missing out on wonderful opportunities to discover and share the past. As proof, I present the “Top Toymaker’s Buying Guide” from Life magazine in November of 1959. Life staff writer Herbert Brean sat down with Louis Marx — described in the magazine as “the world’s biggest and most successful toymaker” — and constructed less of a guide and more of a manifesto on what makes a toy succeed or fail.

Today, a buying guide — such as the ones I posted a few years ago offering up great Christmas gifts for Transformers and Marvel fans — itemizes specific gift ideas. Toys, games, electronics, movies; the gifts may come from any product category, but the commonality across all gift guides is that exact items are suggested as gifts. Contrasting that approach to holiday gift guides is this Life article: Marx and Brean do not provide the reader with a shopping list but do, however, provide guidelines for selecting a toy for kids.

In today’s brand-driven, gadget-focused, Disney-led consumer market it is difficult to comprehend a buying guide that doesn’t actually come out and say “Go buy these seven things.” But that is exactly what Marx and Brean do, with Marx providing six categories parents should consider when buying a toy for their kid.

- Familiarity – In the article, Marx describes familiarity as reflecting reality. “Although an occasional fantasy toy will become popular, children usually want what they have actually experienced in some way.” The 1959 article is offering familiarity as connectedness to the world around us, stating that toy trains and animals need to be realistic. I would argue that familiarity is also important today, but instead of realism today’s sense of familiarity comes in the form of popular brands. Transformers, My Little Pony, and Barbie are all familiar to kids because of the larger entertainment built around them and not due to any sense of realism.

- Surprise – Marx states: “Toys should offer the child something he does not expect.” The article is treating surprise as a gimmick or feature of the toy, not as the surprise of an unexpected gift. I do not believe that in today’s market surprise is required; too many commercials, YouTube videos, and detailed box descriptions eliminate surprise as a feature. Toys that do something may be popular, yes, but gimmick-driven toys are expected these days and not at all a surprise.

- Skill – The whole “simple to learn, difficult to master” concept at play, Marx means skill as something a kid can learn, develop, and perfect because kids “like to display” the learned mastery with the toy. As a kid in the eighties I would have said Transformers fell into the skill category; each was a little puzzle and the ability to transform a toy quickly — without instructions! — was certainly something we shared with each other in ’84 and ’85. Today’s Transformers may be too puzzle-like . . . that’s a discussion for another time.

- Play Value – In the article, Marx describes play value as “what keeps the child occupied for hours in an entertaining or creative way.” This has definitely not changed, and play value is as important today as ever. I’ve chatted with enough parents to know that sustaining the entertainment value of a toy is challenging; toymakers have known this for decades and the growth of product lines decades ago actually extended the play value of individual toys; those Luke Skywalker, C-3PO, and R2-D2 action figures released in 1978 gained new life a little later with the introduction of R5-D4 because kids could now play out a scene from the film in any way they could imagine.

- Sturdiness – Marx addresses both durability and safety in this category, both of which are still important today. The toy recalls of 2007 demonstrated that toy safety will forever be a concern for toymakers and parents. I don’t think toys are any safer or more dangerous than they were in 1959, just that new technologies and gizmos bring new challenges. As to “sturdiness,” most toys today are tough and ready for play as long as they’re kept basic and limit the number of moving parts. Why don’t you give a Hot Toys action figure to a kid? Too many moving parts; just see what Harrison Ford did to a Hot Toys Han Solo action figure and you’ll understand the joints problem.

- Comprehensibility – We can also think of this as “ease of use.” Marx suggests that kids do not enjoy toys that are too challenging or difficult to understand. Of games Marx believes that difficulty is why “most games are not successful.” Things have changed since the fifties, but even today the most popular games in the world are those with a streamlined and well-presented set of instructions. Days of Wonder’s Ticket to Ride has done amazingly well across the world because it addresses both the “skill” and “comprehensibility” factors Marx outlined in the 1959 article. Some things never change.

It’s fascinating that something written about a “fashion”* industry is still relevant almost sixty years later. The more things change and all that, I guess, because it almost feels like all we would have to make is a few tweaks to the Life magazine article to make the text relevant to today’s parents. How many parents these days, though, would consider a gift guide that doesn’t mention any specific toys to actually be a valuable read.

Marx and Brean’s article doesn’t end with “six factors to weigh in appraising a toy.” The article also asks us: “Who actually buys toys, the adult or the child?” Remember, 1959 was dramatically different from today. Barbie was introduced in 1959. Hot Wheels didn’t exist yet. George Lucas had not directed his first film. Hasbro was still five years from launching G.I. Joe. Marx hints at things to come — “They [children] see toys advertised in magazines and on TV, and they put pressure on the adults.” — but even he couldn’t have forseen the growth of toys as entertainment brands, despite Mattel’s successes with TV advertising by that time.

“The money went for newspaper, magazine, and chainstore catalog ads, which was the way companies hawked their products in the golden age of toys, with most of the hype beginning around Thanksgiving and culminating at Christmas.”

— Toy Monster*, Jerry Oppenheimer, 2009.

Marx may have understood the value of advertising, but he hadn’t quite embraced the need to advertise toys. Marx’s media ad budget is mentioned in a handful of different books in my library as only about $300 in 1959, the same year that Mattel bet their entire company and committed $500,000 to advertising on The Mickey Mouse Club. I’d love to find more information on what Marx spent on ads after 1955; this 1959 Life magazine article makes me think the man watched Mattel’s advertising successes and learned from their actions. Unfortunately, I cannot find details to support my suspension that things changed with the toymaker’s thoughts toward advertising.

The article closes with “two things” that are described as things Marx believes in.

Purely educational toys are “just no good.” I think this is as true today as it was in 1959; despite successes with various educational toys and software over the years, it feels to me as if the more successful educational toys are those that teach without being purely driven to educate. This is something that Milton Bradley would no doubt have argued with Marx over, seeing as how dedicated Bradley was to his work in producing Kindergarten materials.

The second “thing” is a statement that is as self-serving as we can expect from someone who made his fortune selling toys. In the article, Marx says that “the average child is not given enough toys.” Go ahead and read the Life magazine article for the exact wording on Marx’s argument as to why kids should be given more toys, but regardless of how he twists the statement around to make it something parents may accept and follow I can’t look past my own cynicism. Marx was a toymaker, and toymakers are of course going to want kids to receive toys with regular frequency. The big bump in sales at Christmas is great and all, but balancing out cash flow across the year is even better. Dependable and regular income rather than an annual spike would make life easier on all of the toymakers.

Marx’s thoughts on toy buying are there for you to read; just click through to the full article and enjoy. I think it’s amazing that Marx would willingly share his experience and knowledge so publicly because there’s no way everything discussed wasn’t considered when designing and reviewing new toys. But share he did, and now we can all benefit from Marx’s thoughts on toys, because everything here is as relevant today as it was when it was first written.

* “[The toy industry is a] so-called fashion business, it is always at the mercy of fad; change is constant, sudden, and rarely predictable, like children themselves.” – Toy Wars*, G. Wayne Miller, 1998.